Only a handful of governments have ever pledged money for those damages from climate change that are beyond the realms of human adaptation, with the idea the rich polluting world should “compensate” vulnerable countries for the impacts of climate change still an explosive issue.

Scotland will announce new funding towards the loss and damage from climate change suffered by vulnerable countries that are beyond the realms of human adaptation, Sky News can reveal.

“We’ll be announcing a further financial commitment to loss and damage,” First Minister Nicola Sturgeon told Sky News during the COP27 climate summit in Egypt.

The additional money will look “in particular at non-economic loss and damage that many countries are suffering,” she said, which could include things like loss of culture and tradition.

Economic losses encapsulate things like loss of jobs from industries collapsing, loss of buildings to hurricane damage or loss of entire communities and towns as sea levels eat away at coastlines.

“That would be a further very significant part of Scotland’s determination to see real progress behind that issue that should have been dealt with many years ago,” the first minister said in Sharm el-Sheikh on the Red Sea.

During the COP26 climate talks in Glasgow last year, Scotland became the first developed nation to pledge finance towards the contentious issue. The promised sum of £2m was small but helped break a taboo around the issue. Since then, Denmark has promised 100 million DKK (£11.8m).

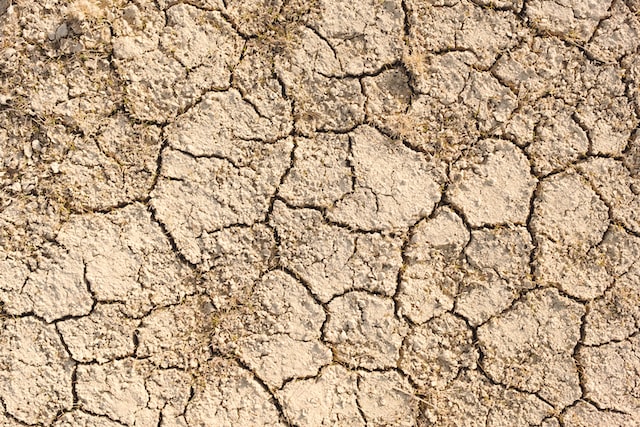

But also since COP26, fierce weather events have hit the world over, from starvation amid drought in the Horn of Africa, to 32 million people uprooted from their homes by violent flooding in Pakistan, surprising scientists with their severity.

Further detail on the new funding will be revealed on Tuesday, Sky News understands.

Addressing world leaders, the secretary-general said loss and damage can “no longer be swept under the rug”.

“Those who contributed least to the climate crisis are reaping the whirlwind sown by others. Many are blindsided by impacts for which they had no warning or means of preparation.”

Vulnerable nations, which research shows have typically done the least to cause climate change but are suffering the worst impacts, have been pleading for financial help for years.

The rich, polluting world, including the US and the EU, has historically been wary of what they fear could be opening the floodgates to endless claims and accusations of liability.

But the devastating impacts of climate change have been so acute, countries have become more open to discussing it, although fiercely resist it being framed as “compensation” or “reparations”.

COP27 opened with a breakthrough yesterday as the issue of funding for such losses made it on to the agenda at a United Nations climate talk for the first time . But countries have until 2024 to come up with a plan, far too slow for some, who point to the savage impacts already being felt, particularly in already debt-saddled countries..

“The first minister’s commitment to help people facing the climate crisis is unparalleled,” said Harjeet Singh, long-time campaigner for payment for such losses and damages and head of global political strategy at Climate Action Network.

Mr Singh told Sky News he hoped the move would “inspire and put pressure on rich governments to recognise the huge gap in funding to deal with climate impacts, such as loss of land, homes and cultures”.

Former US vice-president turned climate campaigner Al Gore, told world leaders he “[supports] governments paying money for loss and damage and adaptation” – a significant statement from someone representing the United States, which last year disrupted talks on the issue.

“But let’s be very clear that that’s a matter of billions or tens of billions. We need $4.5 trillion dollars per year to make this transition,” to clean energy, he said, saying unlocking access to private capital was needed